Nov 14th, 2022

This post is the second part of a 2-part perspective on the Web3 company Frax, completed jointly with Justin Cullen and Dino Mihalopoulos. The top-level TL;DR is that we study Frax from a systems thinking perspective.

We start by analyzing the Frax system itself in Part 1 and then go on in this part to synthesize Frax within the broader system - DeFi banking. Comments, questions, and claims of “you’re wrong” can be sent to any of my inboxes.

Synthesis

TL;DR: Where does Frax, a leading DeFi protocol known for its algorithmic stablecoin FRAX, fit into the larger system that is DeFi banking? We try to understand this system in-depth with a focus on Frax and how it has evolved, as well as how it interacts with other parts like Curve, Convex, Aave, and Lido. There is a temptation to describe Frax in terms of a bank, and we investigate this too.

We were asked for a succinct three line summary. Voila:

- Frax is not what everything thinks it is; today’s Frax relies on their curve/convex exposure and not their original algorithmic stablecoin/equitycoin setup.

- It has rebuilt much of the important legos in DeFi, which is impressive on the one hand because of their product velocity, but on the other hand leads to a question of why would customers pick them over competitors for <waves hands> any of these legos when they’re so interchangeable?

- What they’re very good at is creating interesting game theoretic situations (fairly) manipulating Convex and Curve gauge voting in their favor, so much so that they’re somewhat propping up those two protocols as well vis a vis bribing.

In our synthesis of 0x, it was important to chart the users of the 0x Protocol. It is a central player underpinning all of DeFi’s order flow, and so this involved extensive work tracking who was using it and why. Frax doesn’t have many users in the typical sense of integrated customers. And so we have a very different task, namely to chart how FRAX and FXS flows through DeFi. If we compare FRAX to other stablecoins like USDC, USDT, or DAI, there are far fewer liquid trading pairs and, unlike those coins, there are no services that accept FRAX as payment for goods. Many services let customers transact in USDC or USDT, and some even accept DAI (e.g. the DevCon website). We’ve never seen that for FRAX.

That users have not materially adopted FRAX gave it an opportunity to develop untethered from the usual demands of a stablecoin and find a different purpose as a major player in the flow of assets through DeFi “banks”. These banks include a number of protocol treasuries, but also, and poignantly, through controlling a large percent of the Curve and Convex banks.

Preliminaries: Curve, Convex, and the Curve Wars

Ok, but before we start, here’s necessary background around Curve, Convex, and the Curve Wars.

Curve is the piggy bank for all of DeFi. Its original value add was as an automated market maker where price slippage was ~0% for coins trading close to par. This was ideal for stablecoins. Consequently, it received lots of capital, and people from all around Web3 use it to swap their tokens. Its most famous pool is the 3Pool, consisting of the top three stablecoins - DAI, USDC, and USDT. Today, that pool has $850m of assets, about half the capital of the $1.6bn ETH / stETH pool.

CRV and veCRV - LPs not only get the low fees from providing pool liquidity, but they also get additional CRV token rewards. CRV has value because of voter escrowed CRV, or veCRV. The veCRV token is neither tradeable nor transferrable, but attained by locking up CRV. The longer the lock up, the more the reward. By staking CRV for veCRV, the staker gets 50% of the LP trading fees, boosted rewards, and voting rights of where to allocate CRV reward emissions (called “gauges”). This means that veCRV holders can influence which pool receives the boosted rewards.

The Curve Wars, explained in detail here, was a result of Curve’s popularity and its mechanism for rewarding liquidity providers. The Convex protocol debuted to help retail users earn by locking up CRV without losing their liquidity. After staking CRV on Convex, the token is exchanged for the liquid cvxCRV. This attracted lots of capital to Convex, which became a powerful force shaping where the returns go on Curve through the gauges. Of course, these rewards dominantly went to the pools in which Convex deployed CRV. That too is governed by a voting structure decided by voter-locked CVX, called “vlCVX”.

If Frax was a bank, what kind of bank would it be?

The original Core Frax V1 setup (described in our analysis section here) can be modeled after a commercial bank. Frax issues zero-interest checking accounts with FRAX and get collateral deposits, where the incentive for depositors is an arbitrage. Frax then invests the deposits as they see fit. Each FRAX is a claim on a deposit that can be redeemed anytime. Note that this is a higher risk claim than in other stablecoins like DAI because FRAX is under-collateralized.

A typical bank looks like the following:

- Assets = Cash + Loans / Investments.

- Liabilities = Deposits + Debt.

- Equity = Legally required buffer so depositors don’t get slashed.

Frax is similar:

- Assets = cash on hand plus the invested collateral

- Liabilities = outstanding FRAX

- Equity = -FXS + the profit surplus.

Frax doesn’t pay out interest to FRAX holders so they don’t have to worry about the typical interest rate mismatch problems in banks. They do have to worry about liquidity mismatches though. If Frax invests in assets that are less liquid than Frax’s deposits, there can be a bank run that forces them to issue more equity.

Initially, investors and other market participants gave Frax a small amount of cash, intrigued by the prospect of a slightly under-collateralized stablecoin. In May 2021, they used this to make their own Curve pool called “Frax 3CRV” consisting of FRAX, DAI, USDC, and USDT. This peaked at just over $3bn in assets and now hovers around $650m. How did it rise so fast? This isn’t 100% clear to us, but as we understand, there were DAOs like Temple that bought into Frax’s vision and agreed to buy up a tremendous amount of FRAX. They could do this by buying FRAX in a Curve Pool with other stables, which would be replenished by the Frax Curve AMO minting more FRAX into it for those stables. They likely did this because they were attracted by a great yield from the Frax team in order to grow alongside the Curve and Convex bull run in early 2022.

This happened in parallel with the Curve wars, and the timing helped Frax attain Curve votes. With those votes, they pushed CRV rewards to the Frax 3CRV pool and claimed a small return. They could have kept going in this direction, using the boosted returns from the pool to slowly and steadily get more control without rocking the boat too much vis a vis the stabilizing algorithm, similar to how a bank would control its risk profile. They, like the rest of the industry, would have lost to Convex playing that game. However, they had already debuted Algorithmic Market Operators (AMOs, see our description in Analysis) in March ‘21, which changed the character of this bank a lot.

…But Frax also mints its own currency! Most banks don’t do that. The ones who do we give a special name - Central Bank. Is Frax a Central Bank?

A brief description of Commercial Banks and Central Banks

Central Banks control the price of money in a country by adjusting the terms and availability of their liabilities. The US Central Bank is the Federal Reserve Bank. The availability of liabilities is influenced both by changes in the other components of the balance sheet and by how the Central Bank chooses to respond through its operations. Changes in the balance sheet through time reveal how successful the central bank has been in achieving its goals and how sustainable are its current policy objectives.

Commercial Banks are the institutions that offer normal banking services like deposits, checking and saving accounts, and writing loans to individuals and small businesses. Most people bank at a Commercial Bank, with Bank of America and Chase Bank being examples in the USA. Customer deposits provide banks with the capital to make these loans, and they usually operate under stringent requirements set out by the country’s Central Bank. In most economies, it is Commercial Bank deposits that make up the majority of money by value, with balances held in Commercial Banks being instantly exchangeable for bank notes. This guarantee of direct convertibility into central bank liability provides some degree of trust in the value of such money. A common currency is needed to transfer these balances and in most cases this is Commercial Bank reserves held on account at the Central Bank.

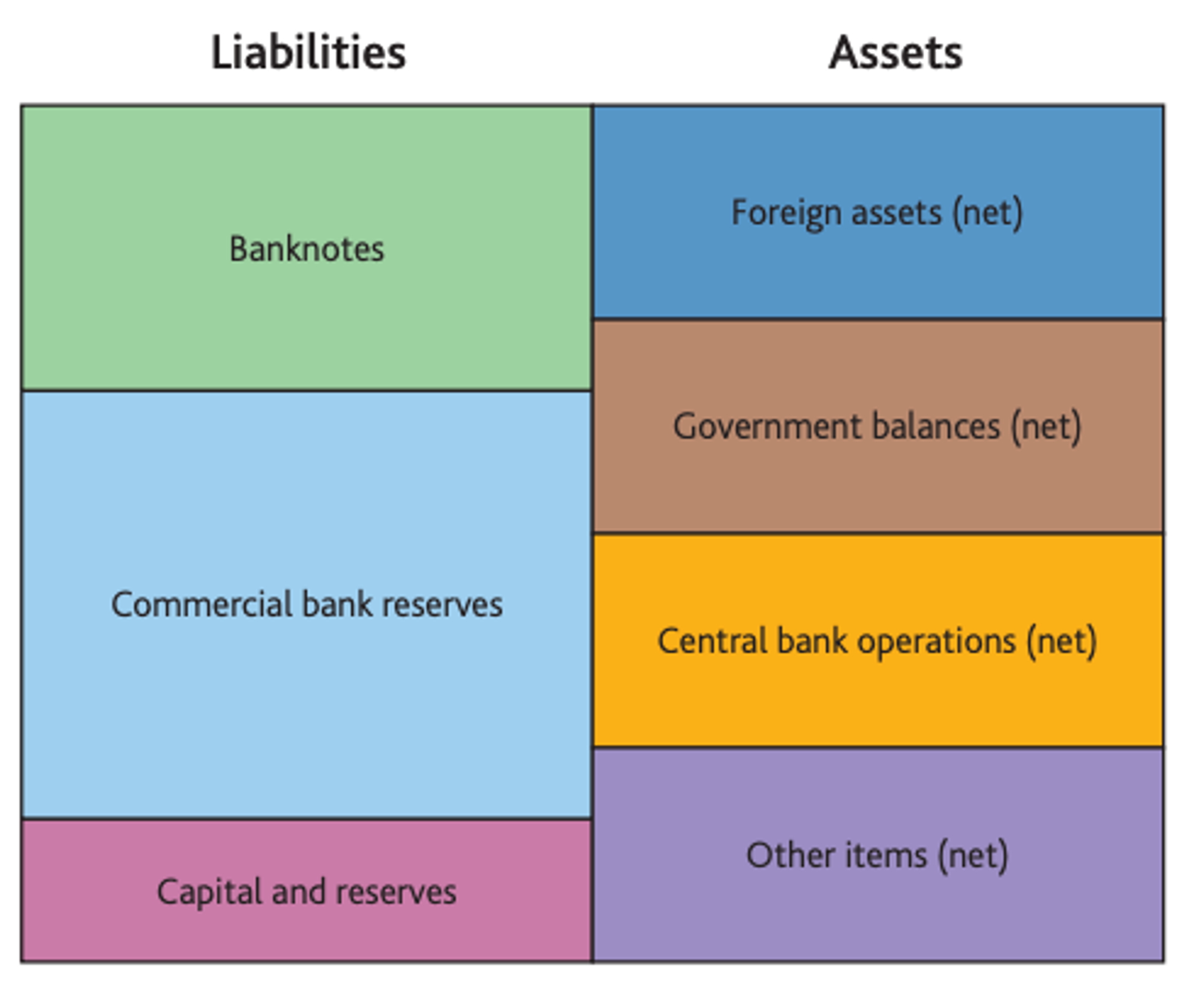

Central Bank balance sheets can be generalized to the following chart.

Banknotes are held in commercial bank vaults, ATMs, or the wider population. They enter circulation via Commercial Banks requests in exchange for reserve balances. Their short term demand is volatile and seasonal, while long term demand is linked to nominal GDP growth. Commercial Bank reserves are overnight balances held as a claim at the Central Bank. Together with banknotes, they are an economy’s most liquid, risk-free asset. Think of them as current account balances held by commercial banks at the central bank just like individuals hold accounts at commercial banks.

Is Frax a Central Bank?

If we squint, the Core Frax V1 consisting of FXS, FRAX, and the FRAX USDC Pool together can be seen as a Central Bank. At any time, it mints currency subject to monetary policy. Squinting further, each AMO is a Regional Bank. They can borrow up to a certain amount from the Central Bank at zero cost and lend it out to pre-defined Borrowers, expecting to get some return on that capital that they then return to the Central Bank treasury. All that time, they must keep a certain collateral reserve ratio. The Borrowers in this story are not controlled by the company and exemplified by groups like Curve or Goldfinch, are the Commercial Banks. They borrow capital from the AMOs at market rates and regularly return profits to the AMOs.

The backing currency here is USDC, equivalent to USD. It's used because people don't trust the system otherwise. You can transfer FRAX into USDC anytime, but the system fails if everyone does so. Like nations moving off of the gold standard, the algorithmic systems want to no longer be denominated by USDC, but struggle to do so because they don't have enough trust, nor an army.

That being said, the analogy breaks down when we look under a finer microscope. First, Frax’s umbrella motivations fit much closer with a private company than with an organization beholden to society’s goals. Its hybrid of operations means that it will take different actions than what a Central Bank would take. If the AAVE AMO stopped making money, or just made a lot less, it would have capital pulled away from it by Frax regardless of if the broader community needed that capital for credit. This article on the differences among banks raises a number of places where these differences shine. For example:

Unlike private financial institutions, Central Banks are not subject to regulatory capital requirements. Commercial banks and other financial institutions are mandated by international and domestic regulations to hold capital buffers directly proportional to the size and riskiness of their lending activities. No such regulations exist for central banks.

While Frax is not regulated with capital requirements by an explicit outside body, it is regulated to do so by the market and its own internal controls. Central Banks have a lot more control over their reserve policy, namely that they can ignore that lever completely and did so for much of the two decades leading up to the 2008 financial crisis.

If a private institution wishes to increase the amount of capital it holds, then it can either retain earnings or go to financial markets to raise additional funds. The ability of the central bank to do this is limited; more often than not the central bank is wholly owned by the government and such choices have wider fiscal implications.

Frax can increase their capital allocation by asking investors. This private institution freedom changes their motivations and actions from what a Central Bank would do.

A further point pertaining to central bank capital levels is that while in an accounting and legal sense, central banks are structured in a similar way to private sector companies, their ultimate goals vary significantly. While private sector companies are focused on profits and maximizing shareholder value, central banks are focused on achieving policy goals.

Frax's ultimate goal is to make money for investors. They are doing this by creating what looks like a Central Bank, but because those goals differ so much, the analogy fails.

It is reasonable for us to think of Frax as having a small, thin, central bank issuing a currency and then a big, fat, operation on top that uses this to generate profits and from where most of the incentives derive.

So what would happen in a bank run?

By bank run, we mean that a sizable quantity who had FRAX asked for their collateral back in terms of USDC and FXS. In other words, the creditors would drain the treasury of USDC. This is ever present for banks and something that their risk control needs to take into account.

Note that the reverse, where FXS holders brought USDC and asked for FRAX, doesn’t matter. In fact, the protocol wants that to happen because then there will be more FRAX in the world, more reserves in their coffers, and less FXS volume.

Frankly, it would be tremendously bad. At a 93% Collateralization Ratio, each FRAX would yield $0.93 of USDC and $0.07 of FXS. The ratio will remain the same, but the protocol would be left with a lot less ability to do anything material.

While there would remain the same quantity of vlCVX to receive income from other bribes and CRV emissions, there would be less money to bribe itself and it would be very hard to fund the AMOs and other entities that require money to make more money.

The confidence in the system would be shook. While FRAX won’t dip below $0.93 because arbitrage, it’s unclear that it would make it back to $1 given how stunted they’d be in what accretive ventures they could undertake. In that world, why would someone trust this to be worth a $1 if they could instead just use DAI or USDC? Equally so for the value of FXS, which is dependent on FRAX having material economic prospects.

This is, of course, different from a Central Bank, and is of prime importance when considering how Frax will act. With a Central Bank, there is a backstop to always generate more revenue, namely through taxes, and so the equity has a stronger claim to value. The only way a run on the bank makes sense in the US is if the economy collapsed. The ephemeral confidence in the American system is what allows the Federal Reserve Bank to lend unlimited amounts to the Treasury. That money is then recirculated in the US to create economic growth, begetting more taxes, and consequently (theoretically) de-risks the Treasury’s credit-risk from recessionary scenarios.

But with Frax, when the supply goes up a lot, those new coins don’t necessarily create new economic growth and certainly don’t create new taxes. As we’ve seen in prior cycles, it instead gets spent on speculation and chasing yield. Sometimes that’s good like the upcoming Goldfinch one where the money is being lent out to other lenders in an effort to diversify crypto money into real world assets. More often, it’s been bad like when levered trading firms borrow and then blow up, e.g. Celsius or Three Arrows Capital.

This is yet another big reason why we likely can’t ever think of Frax as being anything but a for-profit bank that depends on the rather risky business of minting money without the confidence backstop that’s historically been necessary to avoid sudden monetary tragedy.

Today, as we explain in our Analysis section, the Core Frax V1 mechanism is shut off in favor of the AMO mechanisms, in particular with Curve and Convex. This means that a bank run wouldn’t happen by redeeming lots of FRAX for the USDC + FXS, but rather by trading FRAX for the other coins in the Curve pools, which is where most of Frax’s liquidity is held. That doesn’t predict why it would just happen, but says that Frax is susceptible to this problem regardless of how they position their capital.

That’s a good segue into our next section on how they make money with money on Curve and Convex.

How does Frax make money?

TL;DR: Frax provides Convex with a regular and growing source of demand for gauge voting, while Convex provides Frax with a regular and growing source of leveraged influence over gauge voting. This symbiotic relationship increases both of their revenues.

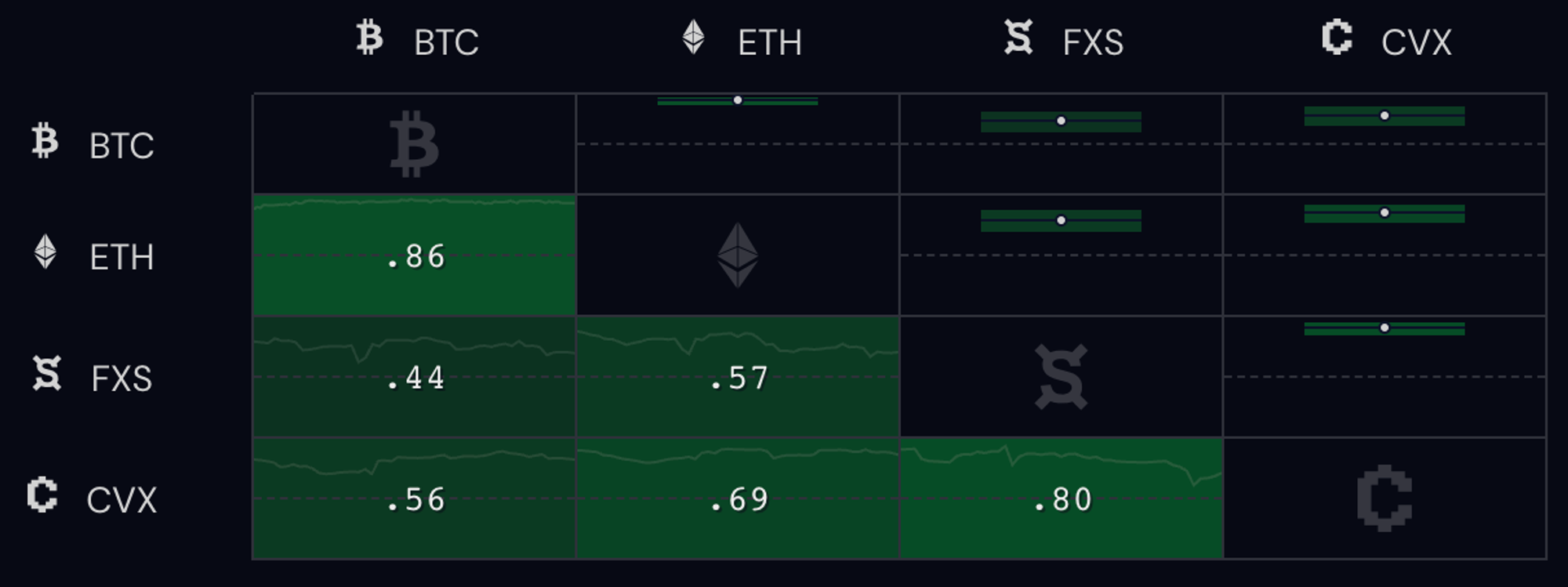

Recall that Convex won the Curve Wars and controls a large lot of the reward emissions. In the three charts below, the first tracks price movements of FXS against CRV and CVX, the second tracks FXS against ETH, and the third shows the correlation coefficients. While in general there is tremendous correlation in the crypto markets, the degree to which FXS and CVX have moved together over the past year is exceptionally high. FXS and ETH are only .57 correlated, CVX and ETH .69 correlated, but FXS and CVX is .80 correlated, almost as high as BTC and ETH (.86). Why is this?

It’s because Frax and Convex own a lot of the same assets and their returns source from the same flows. This is true not only in Curve ownership, but also in (locked) Convex and even (locked) FXS ownership. The charts below highlight this ownership overlap. The first two show Frax’s share of voter-locked CVX (vlCVX) in absolute and percentage basis - Frax controls ~6.4% of the total vlCVX pool, the 2nd largest ownership count and just behind c2tp.eth, the founder of Convex and someone who frequently answers questions in the Frax Finance telegram group. This gives Frax a large say in governance and gauge voting in Convex, key to controlling Curve. It also grants them a piece of the cash flows.

The third chart below shows that Convex controls 15% of voter escrowed FXS (veFXS), the equivalent of vlCVX for Frax. This gives Convex a large say in governance and gauge voting in Frax and a piece of those cash flows. The shared ownership makes support for the other much more likely. Finally, the fourth chart shows how dominant Convex is on Curve, with almost 50% of the veCRV ownership. This is the large underlying source of both of these group’s revenues.

Convex offers Frax something they don’t have, a system for guiding pool rewards to choice targets and a monopoly position in guiding pool rewards in the biggest piggybank in the Web3 world - Curve. Frax wants this because those rewards provide a steady and growing stream of long-term revenue that can further be juiced with bribes (more below).

Frax doesn’t have something Convex is missing and needs, but is the perfect partner in that they want to influence the gauge voting and have a large pile of stable assets with which to do so. Frax can mint pegged assets that can then be invested into select pools as well as bribe other vlCVX holders to do the same. This is in turn a steady source of yield for vlCVX holders.

What does this relationship and the aforementioned assets yield in dollars for Frax? First, Frax makes a certain amount farming CRV. We’ve charted that below on a weekly basis, accumulating to ~$50m since Jun 2021. Frax made another ~$62.5m in that time farming CVX. It’s also made a small amount of farmed $FXS, totaling ~$1.1m. This is all detailed in the following charts, with the fourth showing the first two together and by month instead of week.

However, this is just revenue. To make this money, they have to pay out a small amount in FXS emissions and a significant amount in bribes. Recall that Frax owns ~6% of Convex, which means that they have ~3% of the control of the Curve platform through that share alone. Through this, they can guide 3% of the gauge votes and target their pools for bonus Curve. That’s lovely but also rather small, so they additionally pay vlCVX holders to vote for gauges that Frax want to receive a Curve boost. This helps them target both liquidity increases on Curve for certain pools of interest as well as increases their return given Frax is invested in those pools.

Votium is the major platform for facilitating this bribing. Holders of vlCVX or veCRV can either delegate their tokens to Votium or vote for their preferred incentive through Votium. Every two weeks, aligned with the gauge voting schedule, protocols bribe Votium to vote for delegating their tokens to certain pools. Votium tallies the votes at the end of this time-bound process and votes according to the bribe proportions. Token holders don’t have to do any work and are still paid. Bribers trade $ for votes. Votium receives a 4% vlCVX maintenance fee and a 2% veCRV maintenance fee for running this operation. Everyone is happy.

The following two charts show Votium’s bribes over time, broken down by token, and then Frax’s monthly bribes. FXS is purple and often the largest contribution by a significant amount. In other words, Frax spends a lot in bribes. The second chart shows both the FXS Votium bribes and Votium reclaims in dollars. The latter is the amount that Frax gets back because it too delegates its large (and growing) vlCVX pile to Votium.

With respect to how they determine what and how much to bribe, from a conversation in the Telegram group, the founder Sam Kazemian said:

[Frax has] a formula for the amount of incentives we have to add for each pool to adhere to the FRAXBP rules and also to make it sustainable and economical to bribe each cycle. We usually run those formulas every Sunday since it is more accurate in terms of dollar value. If we run the formula on Thursday for example and FXS, CRV, CVX, and TVLs dump on Curve, it won't be accurate for how much we pay and earn.

There are two remaining negative effects on the Frax balance sheet: a) FXS buybacks and b) FXS emissions. The latter is dilutive to all token holders and on a set public schedule, so it affects token price but not the cash flows. The buybacks are a use of cash flows and used to pay a dividend to locked veFXS holders. This includes the explicit and recently announced $20m token buyback program (of which $4m has been spent according to Sam Kazemian). It is included in the cash flows.

The following table displays this information in one place. Over the past year plus, Frax had a net profit of $20m with a net cash flow of $-4.75m. The net profit includes the farming revenue from the AMOs minus the bribes, while the cash flow also subtracts out the buybacks.

Frax has spent just under $5m to build a large position in Convex and Curve, with support from their shareholders. Returning to the charts above showing percentage ownership of Convex, Frax went from no position on September 15, 2021 to a 6%+ position on October 1st, 2022. The 3,292,718 CVX tokens they control represent $17.7m (both numbers as of Oct 15th, 2022) and is an asset that will keep returning value as long as Convex and Curve are well positioned in the market. They will continue spending money to acquire a bigger position in order to further control Curve, and so veFXS holders need to continue to be patient with their sub 2.5% APR. There are major risks though: a) another player spends even more to acquire a Convex position, b) Curve loses its dominant role as the piggy bank, or c) there is a bank run on Frax. We expand on those risks below.

But first we ask another important question - what would happen if they stopped bribing today and milked the current CVX position? As of Oct 20th, 2022, they have 3,321,656 vlCVX. Stopping bribing FXS pools will reduce a large chunk of their Curve emissions. The most conservative Fermi estimate would say that they don’t get any more emissions, so this 3.32m position is their final count. Today, the vlCVX vote lock revenue APR is 3.65% while the bribe revenue APR is 28%. However, Frax is frequently more than half of the bribe revenue. Without their bribes, and assuming no one steps in to match, this drops to ~14%. The combined APR is then ~17-18%. Pessimistically assuming no vlCVX price growth, this would yield ~$3-3.2m in the next year.

This rate drop would affect Convex and Curve greatly as well. Both of those rely on Frax’s bribing to keep the music going.

Over that time though, Frax would stop building up their vlCVX position. In the past year, their position on a percent basis has doubled given all the bribes. It wouldn’t be fair to think that it would half in the next year - that would only happen if another organization took up the mantle of those bribes. But dropping by 10-25% is reasonable and would mean that they’d make only 75%-90% of that count, or ~$2.25m - $2.8m. Any growth multiple in CVX or CRV, and by extension vlCVX, would be multiplicative here as well.

That being said, they wouldn’t actually do this because they want to keep building their share in vlCVX, not milk it. This is because the goal is to use the CRV and CVX emissions to incentivize users to enter the rest of the Frax ecosystem. This is Frax’s quest for The Holy Trinity.

The Holy Trinity

The three pieces of Frax’s Holy Trinity are FRAX the stablecoin, FraxSwap the swap exchange and time-weighted automated market maker (TWAMM), and FraxLend the money market for lending crypto assets for interest and built on isolated token pairs. These are each detailed in depth in our Analysis post - FRAX, FraxSwap, and FraxLend.

The newest piece is FraxLend. A refresher is that it hosts borrowing markets between any pair of ERC-20 tokens with a Chainlink data feed. The resulting tokens are interest-bearing receipts of deposits denominated in FRAX. Anyone can create pairs between any two assets, but most pairs will be FRAX-based. This is because the only group that really cares about another lending protocol is Frax. But boy does Frax care.

That’s because existing AMO infrastructure gives Frax the option to mint FRAX into over-collateralized lending markets as it doesn’t change the Collateral Ratio. Consequently, users with supported collateral can access a revolving FRAX credit line without needing counter-parties. In return, credit is denominated and paid in FRAX, creating organic demand for it from counter-parties. By users, we really mean DAOs. Groups like OHM, BadgerDAO, and StakeDAO are expected to use this credit channel and get FRAX into circulation, which is what Frax wants. The FraxLend service is free for anyone to use. It makes money when the protocol lends FRAX to borrowers and gets more FRAX into the world.

The third leg of the trinity is FraxSwap, which was designed for Frax to better manage its monetary policy. It’s not imperative that users use FraxSwap for their swapping, but Frax is betting that it becomes natural to do so if they’re already using FraxLend for borrowing or lending. It’s already tied directly into the web experience.

With these in place, they have a protocol with Aave, Uniswap, and DAI wrapped into one. However, why does anyone care? Before we answer that below, let’s first describe FraxETH’s contribution.

How FraxETH adds to the Trinity

We describe FraxETH in our Analysis post. Briefly, it is a competitor to Lido where users can stake ETH for frxETH, a liquid token meant to trade 1:1 with ETH. Frax serves as a mainnet validator and stakes the ETH for yield. Users can stake their frxETH for sfrxETH to get the yield from the validating, minus the 10% percent that Frax claims for this operation, of which 80% goes to the Frax Treasury and 2% to an insurance fund.

The key difference between frxEth and sfrxEth is that while the sfrxETH holders get the staking rewards from ETH, the frxETH holders receive none of that yield. Instead, frxETH holders can stake their tokens in a curve frxETH / ETH pool, which Frax may (periodically) pump with gauge votes. The result is that the frxEth holders have the potential to receive more rewards staking in that pool than the usual validation rewards. The two classes of frxETH and sfrxETH together create compelling dynamics:

Say 100 people minted frxETH for their ETH and put that frxETH into a Curve pool because they were being rewarded at a better rate than they usually would be for holding ETH. This better rate was because that Curve pool was extra incentivized by Frax. At this point, there is a lot of yield being returned to the Frax validator pool from all of that Eth. Then the 101st person comes along and mints their frxETH. They could stake it in the Curve pool, but if they staked it as sfrxEth, then they get not only the yield of their original Eth but also the yield from everyone else who was choosing to stake their frxETH in Curve.

In today’s environment, it’s always advantageous to stake ETH into frxETH over other mechanisms like Lido’s stETH. Most of the time, the yield on sfrxETH will be the same as the yield on stETH. Sometimes Frax will supercharge the Curve frxETH / ETH pool for a couple of months and people will stake their ETH into frxETH for the yield, assuming the pool is saturated with ETH. Consequently, the rate on sfrxEth will also increase for those two months because there will be surplus frxETH. Then they'll stop funding that gauge and people will be left with frxETH. What should they do with it? Either they transfer it back into ETH using Curve, use it in the open market, or stake it in sfrxETH and settle the rate to be similar to that of stETH.

Due to these dynamics, there will plausibly be a market shift from Lido’s liquid token stETH to Frax’s liquid token frxETH and then sfrxETH in order to get the higher rate. Lido can’t match this rate unless they find a way to match the return with another source of funds or sfrxETH attracts too much capital. The latter is metaphorically a great problem for Frax to have, while the former may actually lead to a large problem for Frax if Lido starts investing in CVX.

The once and future Frax vs Giants.

We’ve described a number of offerings that Frax is trying to merge under one unified temple to DeFi. For none of these services is Frax the winner in its industry:

- Lend? Aave and Compound do it better.

- Swap? Uniswap does it better for most coins; Curve does it better for stablecoins.

- Stablecoin? Dai does it better because users trust their over-collateralization.

- Staking? Lido does it better and have years of experience now.

It's a really hard market position to be in when you excel on none of the features in which you're trying to win. Frax does two things better than these other groups:

- The first is their amassed positions in CVX and CRV. These help attract users and capital to their products and create intriguing dynamics, such as the FraxETH machinations.

- The second is their velocity of product output. In the past year and a half, this team has built a collection of legos while operating as a very lean organization burning only about ~$2m / year in expenses. This collection includes the AMOs, the Curve and Convex holdings and bribing operation, FraxLend, FraxSwap, and an entire ETH staking service in FraxEth. With respect to finding a margin of safety in a bet on FXS, it certainly seems like the team is capable of slowing down the game clock relative to what is a very fast moving industry.

For every other aspect they are less well positioned and are attacking behemoths who perceive some of the same promised land, such as Aave and Curve’s stablecoin ambitions. One of Frax’s bets is that there are synergies between these services. For example:

- They have an advantage in lending because they can print FRAX into the lending pools. Until Aave completes their upcoming stablecoin, FraxLend has the potential to acquire users looking for cheaper rates or faster liquidity.

- Another advantage in lending is that they can juice the rates with the vlCVX emissions. These lending pools can be a part of the gauge targets.

- As described in the FraxETH section, they have an advantage in staking due to their plausibly better system (two-tiered vs rebasing) and this is furthered by their gauge control.

- This advantage also applies to swapping where users get better rates via gauge reward subsidies.

All of those advantages depend to some extent on the rewards from the Curve and CVX emissions. Those aren’t infinite, and so decisions of how to allocate them are among the most important strategic questions for Frax. Some of these services will necessarily be emphasized over others.

How do their other AMOs factor into these plans?

To this point, wee’ve limited our discussion to FRAX, FXS, the FraxEth ecosystem, FraxLend, FraxSwap, and the connections to Convex and Curve.

The Algorithmic Market Operators (AMOs) are another material section for Frax. We mentioned in our Analysis section here that there are many AMOs that have been approved but are not yet live, each of whom would push Frax into new business operations. Three prominent examples are all from the same class; Goldfinch, TrueFi, and Centrifuge all pull Frax into lending to real world operations. These provide diversified yield and reach beyond just crypto.

Are these (and others) accretive? It depends heavily on the strength of the downstream asset streams. When they pledged up to $100m to Goldfinch, who on Frax’s team was evaluating the strength of the lenders on Goldfinch’s platform? Who was assessing whether the senior pool or the junior tranches were a better bet? The governance proposal was for the AMO to invest in the senior pool - who was looking into the senior pool dynamics and what it would mean to be a major play in it if the book stopped growing so fast? We could ask a lot of similar questions. The theme of them all is who is acting as the Chief Investment Officer at a company that was originally a stablecoin producer but is now actually a bank making investment decisions and why would that person be fit for this new job?

And it’s not just about each individual AMO bet. They are not isolated because their failures will systemically affect Frax’s credibility. This paper highlights his with respect to banks:

A fall in the value of foreign assets or a rise in long-term interest rates could reduce the value of [bank assets] while leaving the value of their liabilities intact. At some point, the capital could be put at risk, [which can undermine the bank’s credibility]. It is of course the macroeconomic and financial stability of the country that should determine policy decisions of the central bank. It is not profit or loss implications for the central bank’s balance sheet.

He posits this in the context of central banks, which have the benefit of a country’s backing. Frax doesn’t have that benefit and must make its way without. Instead, the paper highlights how risky it is to be doing AMO operations when bringing in assets from far-flung areas of DeFi. When those assets turn bad, this affects Frax’s credibility going forward.

That being said, the AMOs today are small beans compared to Frax’s Curve+Convex business. Their importance is in how quickly they can spin up and interoperate with the rest of DeFi. They grease the wheels, which brings us to Frax’s Flywheel.

Frax’s Flywheel

Here’s a graphical display of the flywheels built into Frax. Check out below for a description. First, a few observations:

- The yield to veFXS holders is very small because that path has only a weak influence on the flywheel and downstream revenues. In other words, it costs a lot to give dividends to shareholders.

- People trading in Frax’s Curve Pools is great and powers their revenues without them doing anything.

- People LPing into their Curve Pools with non-Frax coins doesn’t do anything for Frax except reduce their risk of a bank run.

- An increase in Curve and Convex prices is great for them because it returns higher yields.

Let’s follow the core flows. First, there’s the Frax Controlled Liquidity that goes into Curve Pools. This feeds the Curve Emissions, which can be boosted by Curve Gauge Weights. Those Curve Emissions feed Revenue as can be seen with the light blue “Revenue” arrow. Bookmark that position.

A second entry point is outside capital flowing into FraxETH, which then feeds into any of the Curve Pools, the Staked FraxETH, or the FraxLend Pool. We saw how the Curve Pools reach Revenues, but the FraxLend and Staked FraxEth have similarly clear paths to accumulate Revenues.

From Revenues, we have five options for Allocating that Investment:

- Option one is to receive it as Frax Owned Collateral, then use that to mint FRAX as Frax Controlled Liquidity and continue this loop.

- Option two is to use for Bribing voters on Votium to increase the Curve Gauge Weights, which then increases the Curve Emissions and leads to Revenue on the next round of voting.

- Option three is to do the same Bribing but orient the Curve Emissions to the Curve Pool FraxETH position, which increases the amount of ETH going into FraxETH and increases Revenue later on that way.

- Option four is to Pay veFXS Holders more, which would plausibly increase the FXS price, leading to a small bump in FRAX transactions that ideally ends with a larger FraxLend pool and thus feeding back into the Revenues.

- Option five is to increase the vlCVX position, which again helps increase the Curve Gauge Weights and leads to Revenue on the next round of voting.

There is some subtleties in the top part of the diagram where an increase in some Curve Gauge Weight pools also affects the price of FXS. But that has only a small effect.

All four options have their merits and their relative weighting by the team will determine how the protocol will evolve. Recall that the point of the legos is to entrench FRAX in DeFi workflows. Frax wants FRAX everywhere. They want loans denominated in FRAX, trading pairs relying on FRAX, DAOs stuffed to the gills with FRAX and trading them back and forth. If they can do that, then the protocol can mint FRAX to satisfy that demand. Minting FRAX today is no longer about burning FXS but instead about putting it to work in a yield-bearing instrument. This yield will flow back to a capped number of FXS holders. As yield rises, so does the value returning to those holders, and consequently so does the value of FXS.

A discussion from telegram (twitter thread here) highlighted this. A user suggested creating an incentivized pool to constantly rebalance:

Top 3 FRAX pools in Curve (FraxBP, Frax/3CRV and FRAX/FPi) are doing less revenue for Curve than mim-3CRV, with 10x the TVL. Tricrypto is doing 1000x more revenue (!!!!!) with 3x less TVL than FraxBP I think we solve the problem of Frax not bringing any revenue to Curve (and making the flywheel spin even more) by creating an incentivized BTC/ETH/FraxBP pool, which would have constant rebalancing volume like Tricrypto/GLP

Sam Kazemian’s response was to point out that the bribes they pay out make up for this and that what Frax really cares about is velocity of FRAX:

This is a fair point but Tricrypto isn't a stablecoin of another DAO that is paying veCRV+vlCVX holders every 2 weeks to use Curve liquidity/infrastructure. I agree that more volume is better and it will come as soon as Fraxlend is out and lending+velocity of money increases 10x for FRAX, but you also have to even the playing field and consider that the value veCRV+vlCVX holders are getting for each pool is not solely fees. It is fees and bribes. And the bribes for tricrypto are basically 0.

This is the big plan. FRAX is not so much a stablecoin as a way to garner profits from Curve until FraxLend and FraxEth can take off. And the rewards will help bolster FraxLend and FraxEth’s growth rate.

Three major risks

There are three big risks at this point.

The first underlies the whole operation - Curve loses its position as the DeFi piggybank. If that happened, Frax’s amassed vlCVX position would be worthless because it depends on controlling the flows on Curve.

Curve is quite entrenched, but it’s not out of the question. A sea change in ZK technology may enable this opening. So would legal rulings that affected stablecoins mixing with each other.

It’s unclear if such a market change would happen suddenly or slowly, but in the meantime Frax has no choice but to continue this route.

The second risk is if a competitor spends an inordinate amount of money to acquire a dominant vlCVX position or shift the bribing landscape. Frax realized it was possible to influence Curve through Convex for their own means and built their position alongside Convex building its own position in Curve. They’ve spent the past year developing the pieces to keep growing and fueling itself.

Today they are directly going after some of Lido’s pie, and it would not be a surprise if Lido built a matching vlCVX position. On October 20th, a proposal from Ouroboros Capital appeared on Lido’s Discourse suggesting buying CVX because it is a better option for emissions than Lido’s own coin, with the closing line suggesting:

In conclusion, combining both supply and demand analysis, CVX and CRV appears to have a higher likelihood of outperforming Lido, thereby positioning it as a favorable investment for the DAO vs spending Lido tokens as reward incentives.

A problem here for Frax would be if Lido bought a lot of CVX on the open market and locked it up as vlCVX, then used its stake to vote for stETH gauges on Curve. Yes, this would cost a lot of money, which they can afford. And yes it would increase the value of Frax’s vlCVX stake, but no one is planning to sell that asset, so it’s a moot point. The real concern is how that would then make the bribe wars more costly, the gauge emissions less predictable, and consequently reduce rewards and cash flows.

Here are two other variants of this concern:

- Lido bribes vlCVX holders through Votium rather than buying their own stake. Today, ~50% of vlCVX is locked in Votium, Convex holds ~50% of Curve, and the last four bribing rounds averaged $4.1m in total. If they matched that count, they would take half the bribes, or 12.5% of Curve voting power, for ~$4m. Their treasury shows $31m in Eth, $23m in DAI, and $212m in LIDO, so assuming they don’t tap into their LIDO at all, they could spend $54m to run this operation for half a year given that bribes happen every two weeks. In that time, they’d push a lot of the Curve yield to the stETH / ETH pool, which would severely impact Frax and aid Lido’s return. They could use this to return to build a position or continue the bribing.

- Lido buys a CRV position instead of a CVX position and locks it as veCRV. At today’s market prices, $54m represents a 10.5% position in CRV. Say they suffered only 15% slippage, then they’d attain an 8.9% position in total, roughly 70% of what they would have gotten bribing. With this, they could do the same play as above and build up a position over time.

It begs the question of why no one else has done any of these to date. One reason is that no one else both a) needed to do it and b) built up their stake early enough. Frax needed both a business direction and a place to put FRAX to work when they started buying up Convex in May 2021. They explicitly had a mandate to do something with this free capital that wasn’t too risky. Other organizations either didn’t have such a mandate, didn’t have that kind of free capital, or had much better uses of the capital, namely to grow their own lending/swap/staking businesses. In today’s market, a lot of opportunities have dried up, capital isn’t as free, and growth in those businesses have stalled. Consequently, it’s more likely that they will start seeing competitors try to encroach on this tactic. Helpfully for Frax, only deep-pocketed groups can do so today.

The third risk was discussed earlier and is around there being a bank run. While there would remain the same quantity of vlCVX to receive income from other bribes and CRV emissions, there would be less money to bribe itself and it would be very hard to fund the AMOs and other entities that require money to make more money. This is a general issue for all banks, and it’s not clear that Frax’s systemic risk is any worse than any other commercial bank’s risk. At the end of the day, both Frax and real-world banks are founded upon a dollar equivalent and depend on having some amount of collateral reserve to give customers confidence. Given Frax’s association with Web3, they require having more collateral than most banks.

How would this actually happen given that the original Core V1 mechanism for redeeming has been disabled? It would be through the Curve pools. In non-frax stable assets (USDC, etc), Frax has $200m in the 3Crv pool (/frax), $114m in the Curve Frax/USDC (/fraxusdc), and $51m in the Curve-Convex-Frax FRAX/USDC pool. This equals $365m, which is a large amount of their Total Stable External Assets ($415m). If people wanted to redeem their FRAX for USDC, they can just go to the Curve pools and do this. What would happen in a run is that some number of people would get out this way at 100% before the pool got too imbalanced and then another tranche of people would get a haircut.

Is Frax a good investment?

None of this is investment advice! Please dyor. Perhaps not 15000 words though.

In the FRAX/FXS system, FXS takes on the volatility risk in return for protocol profits and seigniorage. The former are paid to veFXS holders as yield and the latter comes through FXS buybacks or burns if the collateral ratio decreases. As we described in our Analysis write-up, redeeming FXS or FRAX as well as updating the collateral ratio can all only be done by the Frax Team. While this could change in the future, we would be surprised if it does because Frax prefers the new mechanisms. Thus we doubt that FXS will capture any seigniorage and so we analyze the value accrual to Frax only through how protocol profits flow to FXS. As shown in the section on how Frax makes money, those mainly derive from AMO activity.

Briefly rehashing, Frax spends a significant amount of capital bribing vlCVX holders for Curve gauge votes in order to earn more yield on its protocol owned liquidity on Curve and Convex. That CRV/CVX revenue stream then funds or backstops much of the other activity in the Frax ecosystem. Our first step in establishing a valuation framework starts with seeing what we get today. The following charts show Frax farming rewards, first in dollars and then in tokens.

The key variables driving these rewards are Frax’s protocol owned liquidity in pools on Curve and Convex, Frax’s share of Votium bribing, and the Gauge Weights on Curve that result from voting.

The total result has been $109m of farming revenue over the last 12 months. Netting out $93m of bribes gave Frax $16m of profit, most of which was reallocated into FXS buybacks. Those buybacks flow to FXS holders who either lock up as veFXS or provide liquidity on Curve and stake their LP tokens on Frax-Convex. Note that while the net profit appears to be similar to Frax’s accumulated CVX position, we think it is just a coincidence. Frax pays its bribes out in FXS held in the community pool, which allows them to hang onto their CVX rewards.

As of 11/8/22, FXS has a $373m circulating market cap and a $552m fully-diluted market cap. The $16m profit is a 3.4% yield on $470m and a 2.3% yield on $690m. Not all FXS is staked or LPing. There is 36.64m veFXS locked up as FXS for an average of two years (source). For simplicity sake, let’s call that $202m of value as derived from the current price times the number of veFXS. Additionally, there is $61.8m of TVL for the cvxFXS / FXS pool on Curve. Those total $266m of market cap earning yield. If all the profits were evenly allocated to staked FXS, the yield for the last 12 months would have been 5.26%. Of course, veFXS and FXS don’t receive yield evenly; The yield for LPing in the cvxFXS/FXS Pool on Curve is 16.82% vs only 1.63% for veFXS.

While this analysis is nice, it doesn’t tell us anything about the future. Even the recent past is foreboding. The October revenue was $2.4m, only $28.8m on an annualized basis. Furthermore, the bribes outpaced revenue by $700k, resulting in a net loss. The change in revenue was mainly a function of token prices dropping as the number of tokens received has been relatively stable.

Where does that leave us? It’s clear that the yields for any type of FXS staking are not interesting enough to make FXS an attractive investment given the risks. However, two recent developments in the Frax ecosystem might change that - FraxLend and FraxETH.

Again, none of this is investment advice! Please do your own research.

Fraxlend Opportunity

Fraxlend gives Frax an outlet to mint more stablecoins, a source of revenue, and a use case for FRAX. Anyone can propose a new token pair as long as it has a Chainlink Oracle price. If there is a token that someone really wants to borrow against, they can propose it and Frax will lend against it if accepted.

Its TVL is $24m and total borrowed is $6.3m as of 11/5/22. For comparison, Compound TVL is $2.3b and Aave is $5.5b. FraxLend’s advantage is that they don’t charge any protocol fees as Frax monetizes it by directly lending Frax against other tokens. Additionally, FraxLend can theoretically list an infinite number of collateral tokens compared to Compound and Aave, which still have pooled collateral today.

What FraxLend enables is for anyone to borrow FRAX against a yield-bearing token, effectively levering their position. For example, say I have cvxFXS/FXS Curve LP tokens staked on Convex. If Convex gave me a token for my stake earning a 16% yield, I could borrow FRAX against it by depositing on FraxLend. I could then use that FRAX to buy more FXS, stake in the Curve Pool, and then stake the LP tokens on Convex for more yield. I would earn the spread between what I earn on my staked position and the interest paid on my Frax borrow. You could do the same thing with any token, for example Goldfinch Senior Pool LP tokens.

This could be big when risk appetites return; it’s certainly attractive. How big is hard to measure. Say Frax earns mid-single digit yields on a growing pool of over-collateralized Frax. A 3% yield on their lending operations would result in $30m of income on a $1b TVL. On top of that, the FRAX trading activity would increase as it would have a newfound purpose, increasing profits for Frax’s Curve pools. More trading profits in the Curve pools increases Gauge Voting towards those because CRV holders and LPs want to incentivize profitable pools. That gives Frax room to reduce their bribing.

One caveat to this opportunity is that there will be stiff competition. It appears that Aave is positioning their protocol and GHO stablecoin to go after lending to LPs.

Frax ETH Opportunity

FraxETH is going after a big market dominated by Lido. Frax has a clever plan here involving the design of FraxETH and Frax’s power over Curve Gauge Voting.

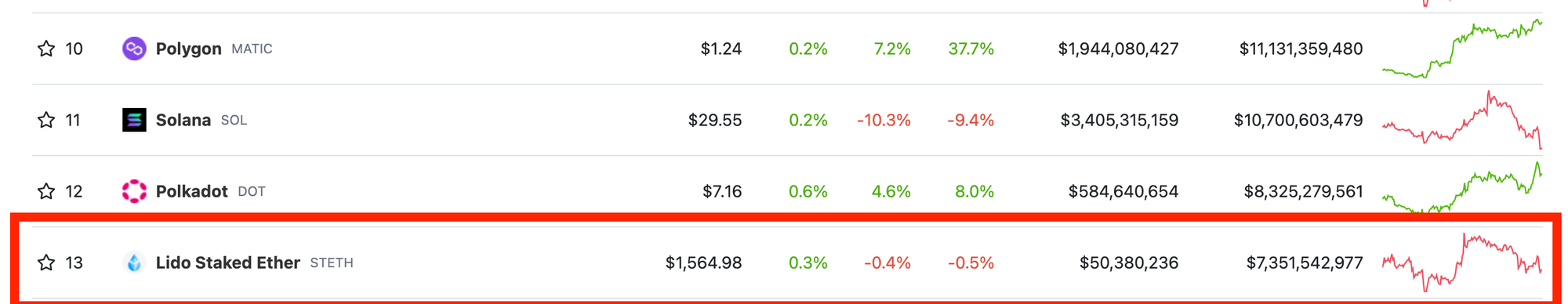

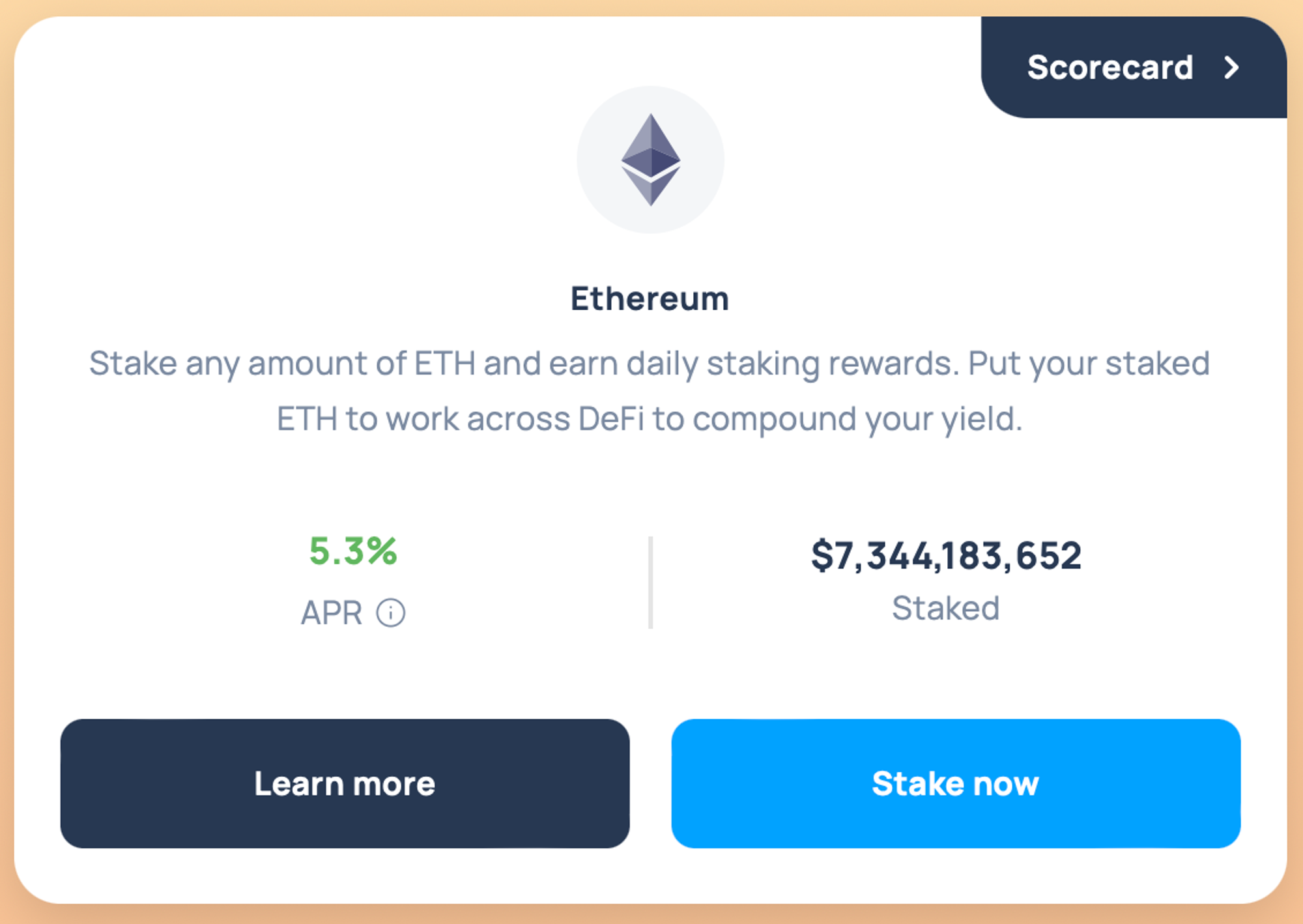

As seen below, the liquid staking derivatives (LSD) market for ETH is 4.944m ETH or $7.8b USD as of 11/7/22. Lido is the market leader with 91.4% of ETH staked through LSD non-custodial protocols and 30.54% market share of the 14,807,623 ETH staked on Ethereum.

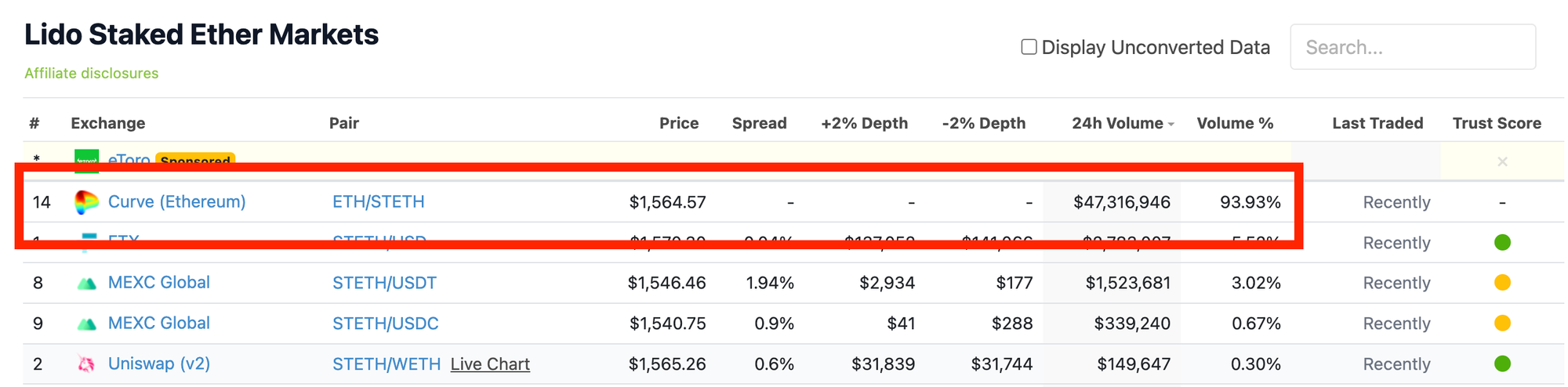

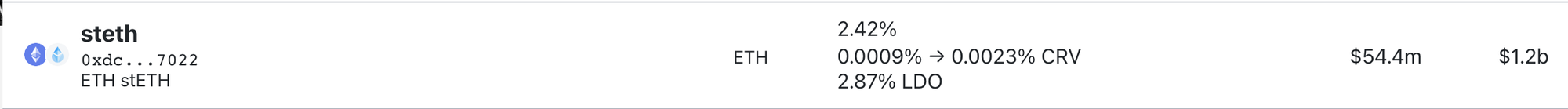

Lido Staked Ether (stETH) is the number 13 coin by market cap. It is supposed to trade close to the price of ETH, and 93% of trading volume is on Curve. This is demonstrated below.

On Curve, LPs in the stETH pool can earn 2.42% base variable APY from trading fees and a 2.87% incentive APY in LDO governance tokens. The 5.29% combined APY is comparable to the staking yield earned by stETH holders.

The 5.3% APR on stETH is inclusive of Lido’s 10% protocol fee, which gets split 50/50 between Lido and node operators. The gross yield is closer to 5.8%.

What’s the opportunity for Frax here and why are they doing this?

Between its CVX stake and bribing, Frax controls the flow of ~20-25% of the weekly Curve Gauge emissions (see chart below). They will leverage that to create a yield chasing game for ETH holders. That game starts with their design for how frxETH holders earn their yield.

We described it in detail in our Analysis subsection, but at a high level the token mechanics for frxETH work so:

- A user can mint ETH for frxETH 1 for 1.

- Once a user has frxETH, they have a decision to make. Either stake it for sfrxETH and earn yield on Ethereum staking (like stETH) or deposit frxETH into a frxETH/ETH Curve liquidity pool.

- If a user forgoes the staking return and instead LPs in the Curve pool, then the yield they would have earned accumulates to the other holders of sfrxETH, boosting their yield.

Frax can juice the rewards for frxETH so that holders get a high yield from boosted returns in Curve Pools. This then juices the returns to sfrxETH as well because there will be more frxETH holders that aren’t staked.

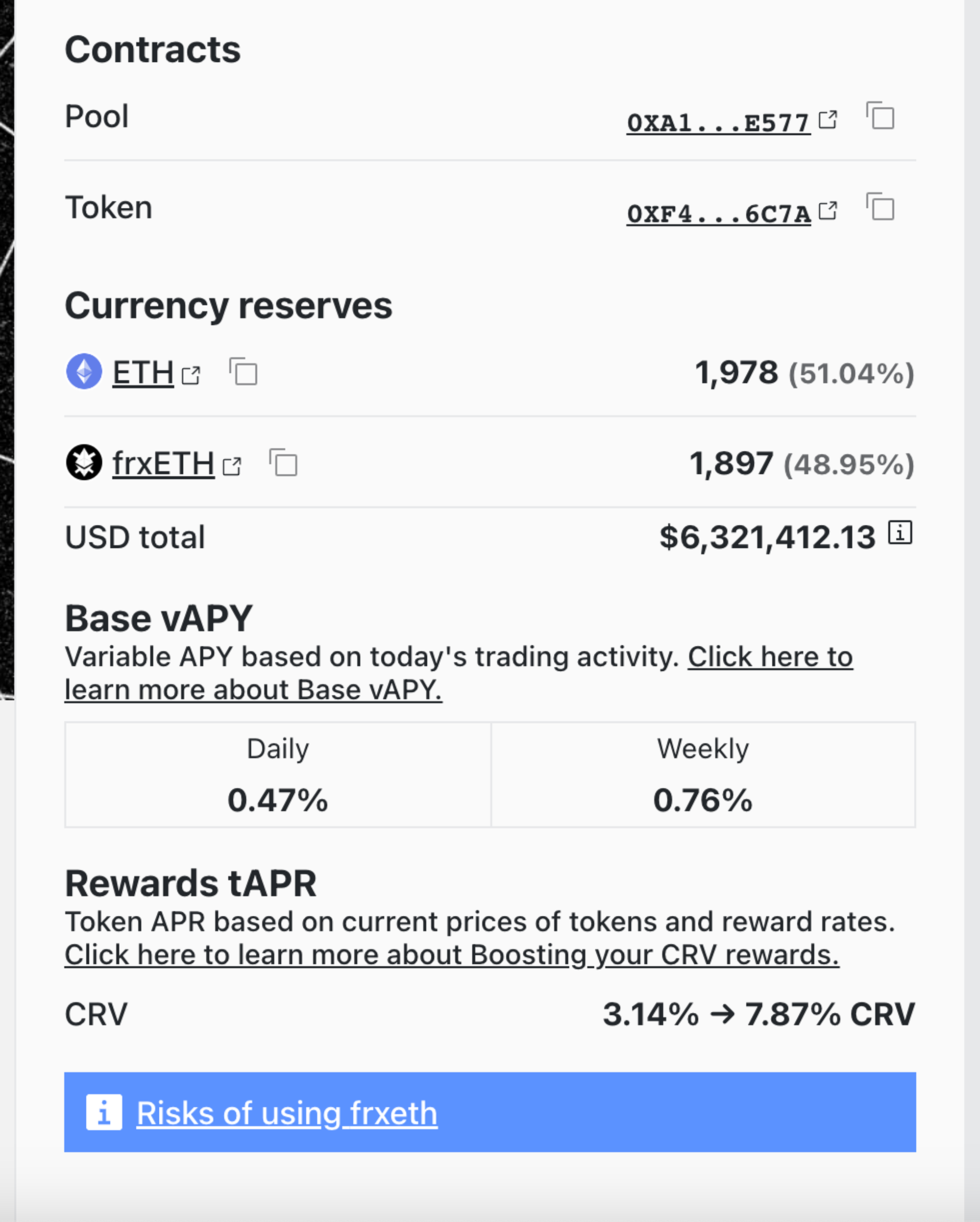

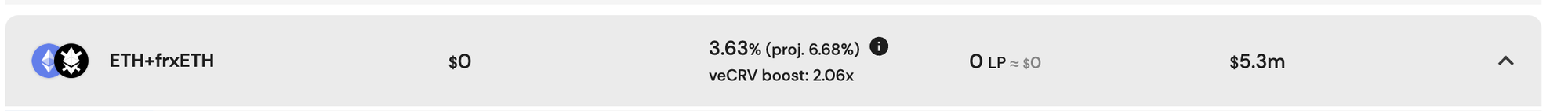

The near term projected APR on Convex for the frxETH/ETH pool is 6.68% and ~8% on Curve, both of which we expect to go up in future rounds of gauge voting.

Like Lido, Frax is taking a 10% fee on that yield, of which 2% goes to a slashing insurance fund and 8% to the protocol. Assuming the same 5.89% gross yield on staking, at $100m in TVL, Frax would be earning $470k in fees. They would need to accumulate $1b in TVL to get to $4.7m in fees and this isn’t taking into account the cost of incentivizing the frxETH/ETH pool on Curve.

While Frax might be able to boost the frxETH yield, we note that Lido still has the following advantages:

- It’s battle-tested and trusted.

- Has a more diverse selection of node operators.

- Has more liquidity and more DeFi integrations.

- Has a large $265m treasury.

This is an uphill battle for Frax, and it isn’t clear that the profit potential is worth the time and capital investment.

Adding Things Together or What You Have to Assume For FXS to Be Attractive

Let’s review some numbers as of 11/8/22:

First, we show on the right side a chart displaying the yield paid to all veFXS holders and LP providers to the cvxFXS/FXS Curve Pool.

This totals $13.99m, which blends to an average yield of 5.26% across both groups. That is a 3.73% yield across the circulating supply of FXS.

We care about both of these groups because they represent the population of yield seeking FXS holders.

Next, below is the Fraxlend opportunity, which is most consequential for boosting yield.

We see that if Fraxlend attains a $500m TVL, has 50% utilization, and earns 7% on its capital, Frax will earn $17.5m in interest income. That would more than double the yield.

Although $500m TVL is 1/10th the size of Aave and 1/4 the size of Compound, it isn’t clear where that capital will come from during the bear market. During a bull market, this could be possible. However, note that Aave is planning a go-to-market strategy for its GHO stable coin around lending to liquidity providers, starting with Balancer LPs. We think this could be a serious headwind for Fraxlend given that Aave has a large and established lending business.

Last, on the right we show FraxETH, using RocketPool as a comparable. This doesn’t seem like a very profitable endeavor given Lido’s monopoly status.

The right side view shows the aggregate, with the caveat that this is not discounted and we are not taking into account how long these scenarios will take to play out. This scenario relies on FraxLend becoming very popular.

Should you take this bet? We leave that answer to you, dear reader, but before we conclude, here’s an experiment to test out FraxLend’s potential.

- Go find the best yield you can get by staking/LPing FRAX.

- Compare that to borrow rates on FraxLend.

- If there is a positive spread, people will borrow FRAX there in order to arb this spread.

Frax can then boost the rewards for depositing Frax into those pools, which will incentivize more borrowing. After this spread closes, are there similar plays available? If so, then the velocity of FRAX will increase greatly and Frax will reap those rewards through FraxLend.

Conclusion

The Frax team is stellar at building products and delivering. However, they’re working from a difficult position. Aave is bigger in lending and is adding a stablecoin to their existing business. Lido is bigger and well trusted. At today’s FXS price, it isn’t clear if FXS holders are getting compensated for the risk involved if these ventures fail.

What could change things?

A bull market would be nice. So would an insight that supercharges FraxLend. Here’s an idea - partner with Damm.finance. They have a mechanism for intelligently under-collateralized lending and are driving on an interesting thesis that will likely be quite valuable in the coming years of Web3 financialization.

At the end of the day, Frax’s strategy seems to be to build a bunch of important legos, efficiently put them together, and then try hard to get one of them to take off through Convex kindling. They are well prepared when something does work for them to take off, but it remains unclear why users will actually care given that none of their products are best in class.